Writing the Silent Battles: Exploring the Impact of Trauma on Veterans and Their Families

Finding answers, closure, forgiveness, peace, and healing through military research.

He cried out in his sleep and thrashed around as if his life was in grave danger.

He was ….. angry, silent, abusive, an alcoholic, out of his mind, emotionally withdrawn……..

He was the happiest father and grandfather with no signs of any war trauma or PTSD. Maybe he hid it well.

I had a horrible relationship with my father and almost hated him. After he died and I learned about his combat experience, I am filled with regret and sadness.

In all the years I’ve been doing World War I and World War II research, with a sprinkle of Korea and Vietnam, I’ve heard clients tell me similar things about their father, uncle, grandfather, mother, or brother that bring a rise of mixed emotions. One client in particular questioned who he himself was after learning about the concentration camp his father helped to liberate. The client and his father had a rocky relationship and many things were still being held close and not forgiven or understood, until the military records were consulted.

Once the client understood the context of his father’s experience, he began to understand why his father was an alocholic and emotionally withdrawn and sometimes violent. Forgiveness and healing began to take place. Added to this was the question the client asked me, ‘If my dad was THIS because of the war and now I know, then who does that make me?’

The identity we assign people in our lives, and even ourselves, can change as we grow, have more experiences, hold on to grief, sadness, regret, anger, or release those things. Even after our veteran has passed away, healing can still take place.

Researching the Ghosts of War

It has been my experience, although perhaps this is beginning to change with the rise of more of us talking about personal and ancestral healing, that when we are trained in genealogy or military research, it is only about gathering facts and evidence. It is only about putting things into our tree with some basic understanding of who our ancestors were. There is an emphasis on making sure we have a paper trail to prove everything. Paper trails are not always possible. We must also use our intuition, heart, and soul guidance throughout our research to read between the lines. See the layers that others cannot, to understand each individual we research.

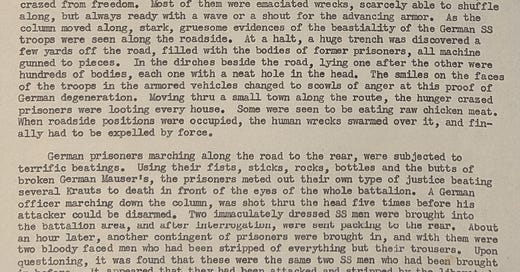

Even I have been guilty of this type of research and lack of understanding about why my ancestors chose what they did, believed what they did, repeated patterns, or that they even carried trauma. It wasn’t until I was more immersed in my spiritual journey and began working more with my ancestors that I understood healing can take place if we step out of the genealogical box. Sometimes this means we have to research the ghosts of war. Let’s look at two brief examples of a veteran’s experience as part of the 11th Armored Division 492nd Field Artillery.

January 1945

April 1945

What might the two examples above help us understand about a veteran who served in this unit and lived with the ghosts and trauma of war?

The veteran hated the cold, snow, ice, or rainy weather - perhaps due to his experience in the horrible winter of December 1944 - winter 1945. Also due to his experience in the cold, maybe he suffered from the effects of trench foot his entire life. Maybe the cold impacted his willingness to do certain winter activities with the family or travel to cold places.

Visiting towns which were damaged by a tornado or other disaster once back home may have caused flashbacks of destroyed villages in Europe.

The veteran may have been unable to tolerate certain smells (stench of death, dead animals, even people) or sounds due to the combat experience. This may have led to him avoiding certain places, people, animals, jobs, and relationships so he wouldn’t have to deal with the smells and sounds that reminded him of war.

Seeing emaciated or very skinny people may have triggered a reaction due to the experience of liberating a camp. Maybe that experience led him to make sure his children always cleaned their plates and were healthy and plump. This experience may explain many dietary or health issues or perspectives of the veteran.

Watching anything where people were being attacked may have triggered PTSD or a flashback or fear, etc., due to watching liberated prisoners deal with their captors.

Alternately, due to the killing that had to be done, camps that had to be liberated, and the enemy who had to be taken as a prisoners and perhaps tortured, this could have turned a veteran cold, angy, emotionally unavailable, even abusive. It could have been too much for some.

Cemeteries and open graves may have created a reaction.

If the American veteran was Jewish, perhaps a form of survivor guilt for being alive after the war because his family emigrated at some point before the war, even if decades earlier.

If your family’s veteran was religious prior to service but not religious afterward, understanding the combat and liberation experience may help explain this change. Alternately, if they were not God fearing prior to service, maybe the service converted them, which could have led down a path of being “too religiously observant.”

Step Out of the Genealogy Box

I invite you to step out of the genealogy box of collecting facts and a paper trail only. I invite you to explore the records that exist to help you put more context to an ancestor or veteran’s life. Use your intuition to guide your search and processing of what you read and learn. Read between the lines and form your own conclusions about how the war impacted your veteran and your family for generations.

When we are able to then read between the lines of what is in the documents and consider the life our veteran lived and how we were impacted by that life, we can begin to see how we may be living some of those beliefs, behaviors, and patterns. We may find we can forgive our veteran of whatever “sins” we feel they committed due to their combat experience.

No one is perfect and in order for us to heal ourselves, our families, and the world, we need to understand what our ancestors experienced, how that may have impacted them, and forgive. Heal.

When we heal one, we heal all.